Episode 1

Arjun Makhijani

President of Science Matters, LLC

Nuclear Waste Disposal Difficulties Plague the Industry

In this episode, Arjun Makhijani, an electrical and nuclear engineer, speaks candidly about the weaknesses of various nuclear waste disposal methods.

Note: This transcript is the raw transcript of this podcast. Minimal edits have been made only for clarity purposes.

Arjun Makhijani (00:11):

If we don’t do that, if we just leave this near rivers and lakes forever, it’s going to ruin the water. It’s going to ruin the land with a very high likelihood. So we need to do geologic isolation.

Narrator (00:25):

Hello, and welcome to Nuclear Waste: The Whole Story. A series designed to explore perspectives of nuclear waste disposal. About half a million metric tons of high-level nuclear waste is temporarily stored at hundreds of sites worldwide. No country has established a permanent home for spent commercial fuel. In the US alone, one in three people live within 50 miles of a storage site. That fact may be surprising, but it’s not for lack of technical solutions. Experts worldwide agree that a deep geological repository would be the best final resting place for this hazardous substance. So what’s the delay you ask? The answers are complex and controversial. In this series, we’re interviewing experts and stakeholders representing pieces of this complicated puzzle to give you a clearer picture of Nuclear Waste: The Whole Story.

In this episode, Emmy award-winning documentary, filmmaker, and Deep Isolation adviser, David Hoffman talks to Arjun Makhijani, President of Science Matters, LLC. Arjun is an electrical and nuclear engineer who speaks candidly about the weaknesses of various nuclear waste disposal methods. At Deep isolation, we believe that listening is one of the most important elements of a successful nuclear waste disposal program. A core company value is to seek and listen to different perspectives on the matter of nuclear waste, nuclear energy, and disposal solutions.

Narrator (02:06):

The opinions expressed in this series are those of the participants and do not represent Deep Isolation’s position.

David Hoffman (02:15):

So Arjun. High level nuclear fuel waste. What are the facts? What is the situation today?

Arjun Makhijani (02:23):

So when you generate energy in the nuclear power reactor, you put uranium fuel in it, and then it fissions. That’s how you produce energy. And it creates very highly radioactive fission products. The two pieces of the fission are very radioactive, most of it. This stuff is so radioactive that if Evel Knievel drove his motorcycle at 60 miles an hour over the 12 feet or so of the spent fuel rod bundles, right after it was taken out of the reactor, you would be dead before he reached the end. This stuff also contains plutonium, but 1% of the spent fuel is plutonium. And if it’s separated from the spent fuel, it can be used to make bombs. And so this material presents very peculiar hazards. It’s both extremely radioactive and dangerous to health. If people come in close contact with it, and then it also has nuclear bomb usable material in large quantities. We’ve got 80,000 tons of this stuff in the USA, and a lot more, a few times more around the world.

David Hoffman (03:42):

Where is it Arjun? Where is it?

Arjun Makhijani (03:45):

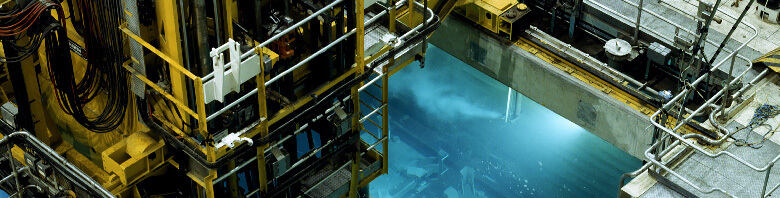

So we have 60 odd sites where we have nuclear reactors and the spent fuel is stored at the reactor site. Because it’s so hot when it comes out of the reactor, they’re pools like swimming pools where the spent fuel must be stored and cooled. Underwater spent fuel pools weren’t designed to hold used fuel worth decades. They were designed for a small amount, spent fuel, and then the spent fuel was supposed to be valuable for its plutonium and uranium content. And that turned out not to be the case. So now what we have is a kind of a very special situation. The spent fuel pools are very densely packed. They put more and more spent fuel in them, 10, 20, 25, years worth. And then when they’re really packed full, they take out some of the spent fuel and store it in giant casks that are dry casks.

David Hoffman (04:46):

Why is this so difficult for the government? You’d think that it’s science that would solve the problem, but apparently, that’s not the case.

Arjun Makhijani (04:55):

The problem with this stuff is so long as it’s stored, you know, it’s, it’s okay. It’s not hurting anybody. The workers you have to take care of. Of course, the workers who are maintaining all that, but all of these materials are corrodable. They don’t last forever. And so the idea was to dispose of it in a deep geologic mine which you know, where it might do less damage.

David Hoffman (05:26):

One, would putting it into something below ground tell me would be safer? And two, everybody knows about Yucca Mountain. I thought that was the idea we’re going to somehow trailer it or truck it, or train it, all this stuff out to Yucca mountain and put it in a big hole.

Arjun Makhijani (05:42):

After looking at all the options for what you could do with this stuff that lasts for thousands or tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of years, was to put it in a deep mine. In my opinion, there’s nothing good to do with it. There’s no safe solution. So when some, when you’re trying to predict for hundreds of thousands of years, your formulas will fail at a certain point. Your containers will also fail. And as we studied this more, as good geologists got involved, rather than physicists, they realize that these containers will leak. So the problem became, how should we package this stuff? And how should we minimize the damage over the long term because we know they’re going to leak. And so where should we put it? Should we put it in Yucca mountain? Should we put it in Hanford? Should we put it in the salt, salt domes in Texas or New Mexico?

David Hoffman (06:39):

What happened? Did that solve the problem? Not perfect as you say, but better.

Arjun Makhijani (06:46):

So the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, I think is a good example of science and politics that were married reasonably well for a very difficult problem. So far so good. But then things started to get screwed up and politics started to enter in a bad way. Partly nobody wants the stuff in their backyard. So in the West, there were nine sites and there were supposed to be narrowed down to three. And then the three were supposed to be investigated intensively and compared, so we could find the best one. Now, as it turned out that many of the sites were in areas, you know, like in the panhandle of Texas, there was a tremendous amount of resistance from the farmers. It’s about the largest aquifer in the country. So there was a lot of opposition.

David Hoffman (07:45):

Was it crazy opposition was sane opposition, in your opinion?

David Hoffman (07:50):

You know, I wouldn’t say crazy opposition. I think there is no, because every site is going to have some problems. And we’re talking about very long period of time. People get very concerned and then you’ve got to bring this stuff by truck or train, as you were saying. And today we are even more aware that, you know, there can be terrorist attacks on these trucks and trains. You could, you could have a real mess. The problem became is that as the pressure on the Department of Energy opposition from politically sensitive places like Texas grew it picked three sites, one in Texas and one in Nevada, the Yucca Mountain site, and Hanford. And the Hanford and Yucca mountain sites had been already scientifically shown to be inappropriate by the National Academy.

Arjun Makhijani (08:43):

So this became a pretty big problem. I, somebody like me who supports geologic disposal, although reluctantly as the least bad thing to do. It became a problem for me because I could not support Hanford and I could not support Yucca mountain because they were transparently bad sites, politically selected. In my opinion, Yucca mountain is the worst single site that has been investigated in the United States. And now I’m not a geologist. So I thought before I say that more publicly as I am doing now, I should ask an eminent geologist whom I know quite well. And I say, what do you think if I say this? Do you think, if you say that I’m wrong, I’ll stop saying it. And he said, well, let me put it this way. If a freshman geology student said Yucca mountain was a good site, I would flunk them.

David Hoffman (09:45):

Well, then I’m glad that scientists are looking at alternatives. And I know you’re an expert at least on explaining these burial ideas.

Arjun Makhijani (09:56):

So we have three concepts now. We had two before and now we have three concepts of how you might geologically isolate this waste. One was this building a mine and, you know, putting waste canisters in it, Yucca Mountain, or Hanford, or some other place. And the other has been since the 1980s known they’re called vertical boreholes. You basically drill a hole thousands and thousands of feet, a couple of miles. And then you put a canister of waste and then you seal that you put another canister waste on top of it. And you have a, basically a vertical pile of canisters that the topmost canister would be quite deep. And so then you kind of seal the rest of it and you have a vertical geologic disposal. The advantages are you don’t have to build a mine. You have one borehole. We know how to make boreholes. The disadvantages, you can’t put a lot of waste in one borehole. So now you need hundreds and hundreds of boreholes. Each one of which has a little bit of damage around which you have to seal, and you have to seal a lot of places and characterize a lot of places. So now the number of places that can be have multiplied, but the amount of waste that we can store at each place has gone down. So become a different kind of problem. Now, as you know, this company, Deep Isolation had come up with a new idea based on fracking technology without the fracking. So fracking technologies. First, you make drill a hole vertically, and then you have a horizontal deviation of that hole that could go out a mile or so.

Arjun Makhijani (11:47):

And they thought, well, we won’t do the fracking. We’ll just take a bundle of spent fuel, put it in a canister and put it in the horizontal part. Now I think that has certain advantages over vertical boreholes.

David Hoffman (12:01):

Why would horizontal be any better than vertical?

Arjun Makhijani (12:04):

Well, because I think the, the path of the waste back up is more complicated. And also the amount of waste per canister is smaller. So this waste is hot. Remember temperature hot. In a mine, when you put a large amount of waste in one drift in a mine, it causes the water around it to boil that’s, that’s how hot it is. Now. You boil, you condense you, boil, you corrode everything. That’s part of the mechanism of leakage. One of the mechanisms. If you have a horizontal borehole with one spent fuel bundle per canister, the thermal stresses on the rocks are going to be lower. So they may not crack as easily, but now you need a very large number of horizontal boreholes.

David Hoffman (12:58):

It seems like something has to be done. Everything is not perfect. You’ve made that clear. There’s expense here. We’re not stopping building nuclear weapons, although God, most listeners of this podcast, hope we do. That’s not where we are. You have children. What do you hope for here?

Arjun Makhijani (13:20):

So the added waste from nuclear weapons is no longer an issue. We’re not making more plutonium for nuclear weapons. The United States, Russia, they all have more plutonium from on the weapons side than they know what to do with. The main problem with plutonium and spent fuel, now new problems is waste from, from reactors. Right now, the spent fuel casks, the dry casks are visible from offsite. They are, they are more or less targetable. They’re not in buildings. They have a very prominent infrared signature, you know, to make it more targetable.

David Hoffman (14:04):

Well, you have people like Bill Gates and others that I believe in supporting nuclear power as one of the solutions to our current energy crisis. Right? So let’s assume that’s not going to go away. Should America, and is anybody in the world going to these newer borehole solutions?

Arjun Makhijani (14:29):

So, you know, geologic isolation is the least bad approach by far. So if we don’t do that, if we just leave this near rivers and lakes forever, it’s going to ruin the water. It’s going to ruin the land with a very high likelihood. So we need to do geologic isolation. We have three approaches. We have the one that has been most investigated, big mines and sealing up the mines, there vertical boreholes and this new horizontal borehole. I think we should investigate all three. It’s quite possible that all three would be needed for different kinds of waste because we have the spent fuel, but we also have plutonium-contaminated waste. We have high-level waste that’s in glass logs. So I think we need a fresh start with the idea that geologic isolation is necessary. And then let’s compare these three things there are pluses and minuses. Let’s make some investment in the new things. Vertical boreholes, I think the government has invested some money. Oak Ridge National Lab has done some studies as to what it will take. And the horizontal boreholes has had very little investment and I think we should invest without putting waste in it. We should invest some real money in looking at the geology, looking at the pluses and minuses, drilling some boreholes, seeing whether we can get the cylinders in and out, how much damage there is around the boreholes, what kind of sealing methods we would use.

David Hoffman (16:12):

There’s always need to be another priority. There’s always a priority that’s ahead of this priority. Should we move up the priority or is this sort of something we should take care of when we have the money?

Arjun Makhijani (16:23):

No, the money is there. So the government’s been collecting the money from nuclear power ratepayers since 1982. And it stopped a few years ago when the Yucca Mountain project was canceled. So the government has a lot of money that is, should be dedicated to nuclear spent fuel disposal, but it is not being dedicated to that. More on top of that, because the government promised to start taking the spent fuel away from reactor sites, starting January 1998 and defaulted on its promise, the utilities have sued the government, and now we, the taxpayers, you and me, and, you know, millions of others are paying fines to the nuclear power plant owners because the government defaulted on that promise and those fines are non-trivial. So we need to stop paying those fines. Start doing, start actually moving forward. We need to get off the Yucca mountain. It’s a bad site. Let’s get a fresh start. Let’s look at these three approaches that we have had and with some dispatch and some real resources going forward.

David Hoffman (17:41):

I want to thank you for doing this with me. Your opinion is very well appreciated by me and I hope by the audiences listening. So thank you, Arjun.

Arjun Makhijani (17:49):

I hope so, David, thank you very much for being on, for having me on your show.

Narrator (17:55):

Thank you for listening. We hope you’ll share this podcast with others and feel free to send any comments or suggestions to podcast@deepisolation.com. You can visit deepisolation.com to learn more. At Deep Isolation, we believe that listening is one of the most important elements of a successful nuclear waste disposal program. A core company value is to seek and listen to different perspectives on the matter of nuclear waste, nuclear energy, and disposal solutions. The opinions expressed in this series are those of the participants and do not represent Deep Isolation’s position.

Nuclear Waste 101

Understand more about nuclear waste and its implications for you and your community.

FAQS

Deep Isolation answers frequently asked questions about our technology, our process, and safety.