Episode 12

Melanie Snyder

Nuclear Waste Program Manager of the Western Interstate Energy Board

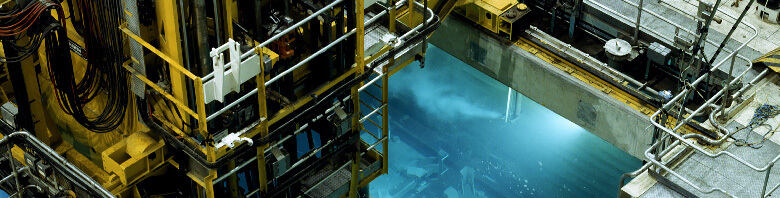

Keeping Nuclear Waste Transportation Safe

In this episode, Melanie Snyder breaks down the complexities of nuclear waste transportation in the United States and offers some insights on improving stakeholders trust regarding transportation.

Note: This transcript is the raw transcript of this podcast. Minimal edits have been made only for clarity purposes.

Melanie Snyder (0:10):

The concern that really comes up most often is just about the safety of it. And I feel like there’s a disconnect between the people who are concerned about safety and scientists and the federal government who typically move these things. And there’s just not always a very good dialogue between these different groups. And I think that’s where the concerns arise.

Narrator (0:38):

Did you know that there are half a million metric tons of nuclear waste temporarily stored at hundreds of sites worldwide? In the U.S. alone, one in three people live within 50 miles of a storage site. No country has yet successfully disposed of commercial spent nuclear fuel, but it’s not for lack of a solution. So what’s the delay? The answers are complex and controversial. In this series, we explore the nuclear waste issue with people representing various pieces of this complicated puzzle. We hope this podcast will give you a clearer picture of Nuclear Waste: The Whole Story.

We believe that listening is an important element of a successful nuclear waste disposal program. A core company value is to seek and listen to different perspectives. Opinions expressed by the interviewers and their subjects are not necessarily representative of the company. If there’s a topic discussed in the podcast that is unfamiliar to you, or you’d like to more closely review what was said, please see the show notes at deepisolation.com/podcasts.

Kari Hulac (01:59):

Hello. I’m Kari Hulac, Deep Isolation’s Communication Manager. Today, I’m talking to Melanie Snyder, Program Manager for Nuclear Waste Transportation and Disposition for WIEB, the Western Interstate Energy Board. The board’s radioactive waste committee works with the US Department of Energy, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and others to develop a safe and publicly acceptable system for transporting spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste under Section 180c of the Nuclear Waste Policy Act. Welcome, Melanie. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Melanie Snyder (02:46):

Hi Kari. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Kari Hulac (02:40):

So let’s start out with a very basic question because I’m guessing that most people don’t know how nuclear waste is transported. Could you walk us through the basics of the process such as common transportation modes, safety precautions, and perhaps you could give an example of how a typical shipment would get to its final destination?

Melanie Snyder (03:00):

Sure. I’m happy to do that. So when you’re thinking about transporting anything, you want to start with some really basic considerations. So what are the physical characteristics of what it is you’re going to be transporting? Where is it located and where do you want it to go? And that’s the same for nuclear waste as it is for anything. Nuclear waste of course has some unique physical characteristics in that it is highly radioactive. So that’s one of the characteristics that you need to take into account when you’re thinking about what you’re going to move. As far as the transportation modes, it really can move, you know, by plane, by a barge by rail or by truck. Those last two by truck and by rail are the most common way of moving them, but you could move it really any way that could be done safely.

Melanie Snyder (03:53):

And like I said, the location is going to be really, really important when you’re thinking about what mode you’re going to want to use. But again, we have to return to the physical characteristics. There’s a couple of different types of nuclear waste that will be moved or that are being moved. There’s spent nuclear fuel, there’s what’s called transuranic waste and there’s, what’s referred to as high-level radioactive waste or maybe tank waste kind of, depending on which definitional framework you are operating in at the time. So when you’re talking about spent nuclear fuel, the physical characteristics of it are that it is very long, sometimes 12 feet long, and it’s heavy because it has to be shielded. So when you’re thinking about transporting it, most of the time, people think that they’re going to move it by rail because the size of it creates difficulties.

Melanie Snyder (04:51):

When you are thinking about moving it by truck, if you think about trying to go around tight corners and things like that, the rail environment allows you a lot more flexibility to be able to move those kinds of packages. When you’re talking about transuranic waste, that’s a special designation that really only exists regulatorily in the United States. Transuranic just refers to elements on the periodic table that are higher than uranium, but in the United States, that’s a special designation that was created to refer to a specific kind of defense waste. So there’s a regulatory definition about, you know, how many curies you can have in that. And the waste tends to be a lot of just contaminated equipment that was used, you know, in the nation’s nuclear weapons programs. So, you know, gowns and gloves and things like that. So when you’re thinking about that kind of stuff it’s not huge, you know, you’re not as concerned about the size of it and going around corners and things like that.

Melanie Snyder (05:52):

So what they typically do is package it in a drum and move it by truck. So that is the typical mode for something like that. You’re talking about high-level radioactive waste or tank waste that is a whole other beast entirely. And what you, or what the Department of Energy and what scientists have considered needs to be done for that is a lot more processing to make it safe for transport and disposal. So depending on which tank waste you’re talking about, you’ll probably have to vitrify it, which means turn it into a glass, but then it would probably still go in a similar type drum, like what we were talking about for the transuranic waste and it would probably still move by truck. And you’re talking about the difference between rail and truck transport. Obviously, the physical characteristics are a really key part of that, but you also have to think about what you can do as far as routing and where the waste is located. So if you want to move something by rail, you know, you need to have rail infrastructure available. So is that going to be feasible? What, what kind of infrastructure improvements might you have to think about if you really do want to move it by rail. Trucks afford you more flexibility because there’s a lot more roads than there are railroads. So that might also play into consideration.

Kari Hulac (07:17):

So let’s say today I have a shipment of spent nuclear fuel that needs to go somewhere, you know, is that a process where there are a million steps, it seems like it would be a bit complicated. Maybe just kind of give a little color about, you know, the process that has to happen for that to be successful.

Melanie Snyder (07:36):

So think about spent nuclear fuel. Obviously, it’s highly radioactive and you’re not really going to want to get close to it. So there’s logistical considerations that get played into when you’re thinking about how you’re going to transport it. So it’s not as if you can get in there and touch it or get close to it. So you do need to have remote operating procedures for packaging. So that’s a key thing in transportation is the package. You have to put the waste into something else in order to transport it. And the packages are not only to protect from radioactivity, it’s also to protect the stuff inside from the vigors of transportation, I guess you would call it. So it is complicated. You have to take the spent nuclear fuel from where it is and put it into a transportation overpack, and then get that overpack onto the rail car.

Melanie Snyder (08:40):

So we’re just going to be talking about rail here since that’s typically what we’ll be using for the spent nuclear fuel. And then that those are the physical considerations that go into the moving of the spent nuclear fuel. You are also probably going to have inspections. So you need to coordinate with whatever entities are going to be doing those inspections. There’s going to be security involved. So you have to have security accompany you along the route, and, and you’re going to have to know where it’s going. So you’re going to have to have a route that’s been planned out. So there’s a high level of coordination and planning that has to go into it, even aside from just the straight physical considerations of transport.

Kari Hulac (09:25):

So I was reading that there have been more than 3000 spent nuclear fuel shipments in the U.S. and about 24,000 worldwide over several decades, how much spent fuel and other waste is currently being moved in the U.S., and to where and how is this expected to change if it is going to change in the coming years?

Melanie Snyder (09:47):

So as far as spent fuel, there’ve been some unique programs in the U.S. where spent fuel has moved. One, in particular, that’s been ongoing for at least since the fifties is the Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program. And the spent fuel that they move from the nation’s submarines and aircraft carriers, and that is a highly successful and highly regimented program that the Navy runs. And so I would say probably less than 20 shipments a year of spent fuel. And of course, it depends on when they have to refuel and what’s going on with the fleet and everything like that. And that fuel all moves to the Idaho National Laboratory under basically top-secret or whatever privacy designation those shipments operate under, but it still is a program that requires a high degree of coordination. The Navy works really well with stakeholders to make sure that people are, you know, prepared for those kinds of shipments.

Melanie Snyder (10:48):

So that’s, that’s one small example of a spent nuclear fuel transportation program that is ongoing, and that continues to this day. And there’ve been some small shipments of spent fuel depending on typically the Department of Energy has different programs. So sometimes they have to move fuel around depending on what reactors they are running and what facilities they have available to store that kind of spent fuel. Those are really sort of one-off shipments and they still require coordination and all the necessary security and everything like that. But it’s not a great example of large-scale transportation.

Melanie Snyder (11:27):

When you’re thinking about commercial spent nuclear fuel, that started the nation’s power plants of which there are about a hundred in the nation scattered all around. You think about bringing them all to one consolidated location, whether that be interim storage, whether that be deep geologic disposal, that’s a much larger scale transportation program than what has been conducted in this nation before. So when you ask about how that might change in the future, if such a facility were to become available, then it would be a much larger scale spent nuclear field transportation program that would be contemplated.

Kari Hulac (12:05):

Maybe talk a little bit more now about what the Western Energy Board Committee is working on right now, and maybe tie that into some of what we’ve been talking about. Some of the examples that you’ve been talking about.

Melanie Snyder (12:17):

Sure. So the Western Interstate Energy Board or WIEB High-Level Radioactive Waste Committee is a group of Western state representatives who have been engaged on this issue since the 1980s. So since the time of the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, which was really when the prospect of this large-scale spent nuclear fuel transportation program seemed imminent. And certainly, there were a lot of steps that needed to occur before transportation could occur such as actually building the repository. But when the state saw that this could occur at some point in the future, they saw a need to come together to engage with the Department of Energy and with other entities on this large-scale transportation program. So the High-Level Radioactive Waste Committee has been engaged since the 1980s on this, and it’s taken various forms as the program has shifted. When it seemed when the program was much more active, you know, they were directly engaging with DOE as far as offering comments on different plans and things like that. And that’s still something that we do to this day. It’s just at a reduced scale since the program really isn’t moving right now. So we still stay engaged with DOE you know, we’ve developed some policy papers to kind of consolidate our historical views about, you know, the best way to conduct this, this transportation.

Kari Hulac (13:50):

So now that, so we’re talking about Yucca Mountain, right? So now that, that is uncertain. Are you planning, is it interim storage that you like moving to interim storage or, you know, what are you, where are you seeing? Is it kind of all on hold right now? Or are you seeing transportation anywhere? Are you planning for transportation anywhere?

Melanie Snyder (14:13):

The interim storage situation is an interesting one. So, you know, for so long, the States and the tribes were really engaged with the Department of Energy. And it’s always been this expectation. The federal government is going to move it and like, those were all the relationships. And that was where all the focus was. And the interim storage prospects kind of challenges those established ideas and those established relationships, because they are looking at moving it without the federal government’s participation, which really does change the environment a little bit. And there’s still expectations that the States have, or the Western States have for being involved in the transportation planning, but there’s not the same environment where the private entities feel like they have a responsibility to engage with the Western States. So, you know, the High-Level Radioactive Waste Committee has invited some of the representatives from the companies that are looking to open these interim storage facilities to our meetings.

Melanie Snyder (15:19):

You know, there’s some, some relationship building there and some information sharing, but as far as the connections and the historical engagement, it’s really not there. So certainly it’s still very important to the Western States. I mean, it’s still the same transportation and it’s still the same stakeholders. It’s still the same people who would be affected. So our interest has not diminished at all, but the environment is a lot different and the expectations are different. And it’s sometimes challenging to handle that kind of pivot, especially when you get the impression from the private entities that they may not be as interested as engaging. That they will meet the regulatory requirements. And that, that is, the metes and bounds of what they feel like they need to do as far as the transportation planning is concerned.

Kari Hulac (16:15):

Right. That, and that kind of raises one of my questions. You know, there has never been a radiological release due to an accident, but the transportation of the materials, understandably, a very sensitive topic for many people. So what are some concerns you hear from the public and how does your organization work with communities that are on transportation routes to make sure everyone feels prepared and trained and safe?

Melanie Snyder (16:45):

Concern that really comes up most often is just about the safety of it. And I feel like there’s a disconnect between the people who are concerned about safety and scientists and the federal government who does typically move these things. And there’s just not always a very good dialogue between these different groups. And I think that’s where the concerns arise. And certainly, you know, radioactivity is this unique thing that you can’t see. And even if scientists feel it’s very well understood, I think it is pretty well understood at this point. And it behaves in pretty predictable ways. It still is frightening to think about these materials moving through your communities when you don’t have a good sense of, well, when you actually, when you don’t trust, when you don’t trust the scientists and when you don’t trust the federal government, and there’s a legacy of national security interests covering up, or keeping secret a lot of the details of the nuclear weapons programs and things like that.

Melanie Snyder (18:00):

There’s things like Rocky Flats that have bred distrust. So certainly between the public and the federal government, when you’re talking about issues surrounding nuclear power, there’s a lack of trust there that merely understanding how radiation works is not going to breach. There needs to be relationship building. And I think the federal government has gotten a lot better at it over the years. They still sometimes operate under the auspices of national security and, you know, sometimes that’s justified and to do that. But it certainly doesn’t build trust. And then when you’re thinking about people’s relationship with science, there’s a different kind of disconnect there where scientists can sometimes be dismissive of the concerns of people that they don’t think are as well informed as they are.

Melanie Snyder (18:50):

So the message that the industry tends to share is that we can do it safely, we have done it safely, shut up. And that’s not effective. It’s just not effective. And I’ve said this before, and I’ll say it again. People’s fears are justified, nuclear things can be destructive. And so we just have to continue to engage with people and continue to keep those open dialogues open and be as open and transparent as possible to help allay those fears. As far as how we work with stakeholders, we work with state representatives who are often in their public health agencies or in transportation. And these are the people who are connected to their constituents. Something that we often hear in our transportation meetings is that the most trusted public official is the fire chief. And if you have talked with the fire chief, he knows where the shipments are coming from, he knows how safe they are, he knows his people are trained, he can relay that information to everyone in his community, and they’re much less likely to be afraid of what’s going on because they feel like someone they trust trusts these shipments. And so our engagement really hopefully trickles down all the way to that level.

Kari Hulac (20:10):

That’s so interesting. I, you know, one of the things I wanted to ask you about is I’ve heard that it can take years to plan the routes and train emergency responders. So I mean, maybe explain a little bit about that process. Might make people at least understand how they could feel safer, even though it is like you say, legitimately scary for people in those communities because also it’s tricky. I know I’m understanding. I think you said earlier, it’s, it’s, there’s a security issue. So the routes are not public for good reason, correct.

Melanie Snyder (20:43):

Well, it depends on what routes you’re talking about. And so it is considered security sensitive information when you’re moving, spent nuclear fuel. The funny thing about that is there’s not that many routes that are available when you are looking at the rail environment. So it’s sort of an open secret in some ways, but yes, and not, there are designated individuals who are privy to that route information and not everyone gets to know. As far as preparing people along the routes, there is a lot that goes into that. There are radiological trainings. So, you know, teaching people along the routes, how to detect radiation and how to deal with it which requires equipment. And if you want to be training someone effectively, you should probably be using the same equipment. So there needs to be coordination as far as what the equipment you’re using.

Melanie Snyder (21:35):

There’s often training exercises that takes people through the motions of what this response would look like. So they feel like they are prepared to do this and there’s turnover. So you have to keep doing these things over and over again. You can’t just, you know, check the box that says they’re prepared because we went out there two years ago and showed, you know, a subset of the responders, how to use this equipment and how to respond to a radiological emergency people, move and things change. So you have to consistently keep up with the program. And that’s something that I hear from my state representatives quite a bit is the difficulties of keeping people trained because of the turnover and the scheduling and all the pieces that go into that. So not only do you have to keep it up, but you have to look all along the route to make sure that you are prepared everywhere, and that’s going to be easier in some areas than others. I mean, there’s challenges when you are moving through population centers, but when you are moving through population centers, you’re much more likely to have people be trained for other reasons. When you are in the more rural areas, you know, further out West, quite frankly, where populations are spread out, you’re going to be more challenged to be working with smaller departments and things like that who probably don’t have access to the same equipment. And don’t, haven’t had the same kinds of opportunities for training.

Kari Hulac (22:58):

Well, I was thinking about asking the question about the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico, which I would imagine is more rural. And I imagine that’s in your 11 state territory, is that correct?

Melanie Snyder (23:10):

It is indeed.

Kari Hulac (23:11):

Yeah. So maybe explain some of the issues that have come up for that plant. For those who don’t know, it’s a mined repository that takes certain types of defense waste.

Melanie Snyder (23:21):

That transuranic waste that I was talking about earlier. That’s where that goes. Yes. Yeah. And those issues that I was just discussing, I was honestly drawing on the WIPP example because WEIB actually just assumed management of the WIPP Transportation Technical Advisory Group. So I have been so much more engaged in working with that group. And it really has opened my eyes to some of these strategic and operational difficulties. And it just requires that you stay on top of things. But certainly, like I said, keeping people trained along the routes is a, is a constant challenge for the States finding funding for supporting those activities. You know, and it’s not just the emergency responders that need to be trained. Medical personnel at hospitals also need to be trained so that there’s a continuity of care. If there is an incident where people can, you know, receive care at the site and then be transported to a hospital and still receive the requisite care and, you know, radiological issues are unique. So the, all the staff needs to be apprised of the unique characteristics of that and, and trained on the equipment as well. So there’s a high degree of coordination and planning that needs to go into all of this. And certainly the WIPP example is a wonderful example of just how much needs to go into this planning.

Kari Hulac (24:50):

And now you’ve worked with, I mentioned a couple of times you’ve worked with a lot of different States in the U.S. do you have ever have challenges in getting them to agree? And what have you learned about working with such a diverse group of stakeholders?

Melanie Snyder (25:03):

I feel very fortunate that the state representatives that I work with tend to agree about what the requisite pieces of a successful transportation program are. And a lot of times their experience with the WIPP transportation program will lead them to the same kind of conclusions for spent nuclear fuel transportation programs. So, the WIPP transportation program really was supposed to be, I mean, obviously its own entity, but also a model for how a spent nuclear fuel transportation program would operate. So a lot of the state representatives that I work with because they are so closely involved in the WIPP transportation program, really just take those precepts and put it into our policy papers and our policy considerations for spent nuclear fuel.

Melanie Snyder (25:57):

And a benefit of working with state representatives and people who are sort of a step below elected officials is that they don’t usually have to bring the political aspects into it. That will change depending on what it is we’re talking about, but it’s also advantageous to only focus on transportation. If we decided that we wanted to try and get involved in the siting space of where a repository would be, that would be a much more complex issue that would probably lead to disagreements between the States, because they have different ideas about what they would like to get out of their States. And sometimes they’re targeted for disposal or storage. So that creates some conflicts there.

Kari Hulac (26:43):

That makes sense. What about the funding piece of how all this is pulled together? Does federal funding impact the work that you’re doing? Any concerns about that or how does that process work?

Melanie Snyder (26:59):

It absolutely does. So we have been fortunate at WEIB to receive funding from the Department of Energy to allow us to, you know, run the High Level Radioactive Waste Committee, but it hasn’t always been the case as I, I have heard that sometimes funding was not available. So activities really did have to ramp down. I think the federal government is pretty good about acknowledging the value of these kinds of stakeholder relations, especially when you’re talking about something as high profile as spent nuclear fuel, and when it provides them a bridge to the people who are most concerned. And certainly it’s not just the public. I mean, think about an elected official in state government who doesn’t engage on this issue and suddenly the profile of it is raised for whatever reason, who are they going to go to, to ask about the safety of these shipments and to, you know, relay information to their constituents and then take a position on it.

Melanie Snyder (27:57):

Hopefully they’re going to go to people who are in their state agencies, and hopefully those people are going to say, you know, I’ve been engaged on this issue for a certain amount of time. You know, I am comfortable with this program. I am familiar with it. So there’s value on both sides, as far as engaging with the public and engaging with elected officials for the Department of Energy to, and the federal government to maintain these, these stakeholder relationships is kind of what they refer to them as. There are strings attached, of course. So we were talking about interim storage because that’s not a Department of Energy program. We are not allowed to use their funding to engage on that issue if they were brought into that transportation program that would change. But as it stands, now we have to use another funding source to be able to support that kind of engagement and not every entity has access to that kind of funding. So WEIB fortunately does have a little bit of funding available to support those kinds of activities, but that is not always the case. And you do have to keep an eye on where your funding sources are coming from and what they are designed to allow you to do.

Kari Hulac (29:15):

Southern California Edison, a utility that’s decommissioning a nuclear power plant known as SONGS just released a strategic plan for relocating it spent nuclear fuel along with a transportation plan. So I imagine you’re know, I know this just came out. You took a quick look at it. Could you share your initial impressions? Does this report align with your process? Maybe just share a little bit about your initial thoughts about that.

Melanie Snyder (29:41):

I did look at the stakeholder engagement piece and the transportation plan, and then the general transportation recommendations contained in the shorter documents and no surprise that it looks like Southern California Edison has done a very thoughtful job about thinking about these issues. So the stakeholder engagement piece in the transportation plan acknowledged the success of the WIPP transportation stakeholder engagement process, and also talked about how the Navy has successfully engaged with stakeholders. So those are certainly model programs that a spent nuclear fuel stakeholder engagement process could be modeled after. So certainly appreciate that they have seen that and recognize the success of those programs. And I also appreciate the transportation readiness pieces. So making sure that onsite infrastructure is maintained or at least that that is a part of the decommissioning process that they’re thinking about how that future transportation will occur.

Melanie Snyder (30:44):

And honestly, one thing I really, really appreciate about Southern California Edison is their inspection program and how they are really ahead of the game, as far as the inspection and repair of their storage canisters, which will have an impact on the eventual transportation. So mostly right now, the activities are focused on extended storage, you know, making sure there’s no cracks and if there are cracks, they know where they are and they know how to repair them, but certainly for transportation, that’s going to be equally as important. And so I think that, that program will serve them very well in the future once they are considering transportation.

Kari Hulac (31:27):

Great. Thank you. So I know this is such a complex issue and I am sure we couldn’t cover it all in just the short podcast, but is there anything else you’d like to share with our listeners?

Melanie Snyder (31:41):

I guess what I would say is that spent nuclear fuel and other nuclear waste can certainly be transported safely. Just requires a high degree of coordination and planning. And if you put the time in, there’s no reason why you can not do it safely.

Kari Hulac (31:57):

Great. Well, thank you so much for joining us today. Thank you.

Melanie Snyder (32:00):

Thank you for having me. It’s been a pleasure.

Nuclear Waste 101

Understand more about nuclear waste and its implications for you and your community.

FAQS

Deep Isolation answers frequently asked questions about our technology, our process, and safety.