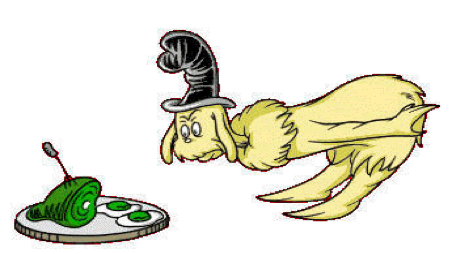

I would

not like it

Here or there.

I would not like it

Anywhere.

Nuclear waste. It has been with us for over six decades with nowhere to go. The first nuclear power plants came online in the United States in the 1950s. The push at the time was to get the plants operational and address the production of nuclear waste as a problem to be solved thereafter. It is now 60 years later and the questions of when, where, how, and for some even why, continues.

Many believe that it is morally wrong to continue production of nuclear power as long as there is no certain path for its disposal. Others are advocates of nuclear power who believe it can be safely stored while we work to solve the problem. And then there are those (like me) who believe the problem needs to be addressed and solved regardless of whether

Unless you have been “in the dark or on a train” you are aware of the fact that there is no present workable solution to dispose of our nation’s growing inventories of nuclear waste. Around 90,000 metric tons and growing. There have been policies and plans set in motion to do so, but they have all been stalled primarily for social and political reasons.

In the U.S. as well as in other countries faced with this problem, the scientific consensus is that the best disposal solution for the waste is in a deep underground repository. Although this is the goal most are pursuing, there is not one high-level waste repository to date that is operational. Finland is the closest to doing so at the Onkalo facility, but even that is not assured.

I have been in some conversations this past year in which people are floating some alternative means of disposal. And why wouldn’t they be – it has been a half-century since the first method was chosen. These ideas range from shooting it to the moon, burying it in the deep seabed,

I would

not, could not, in a volcano.

Not in an Ice Sheet. Not on a moon.

Not on an island, not in the deep sea.

I do not like it, Sam, you see.

As far-fetched as they may seem, these and other options were all considered for the management and disposal of spent fuel. This review of alternatives began in 1957, when the first National Academies study on the subject was published, to 1982 when the Nuclear Waste Policy Act put the choice of disposal in a mined deep geologic repository into law.

There is no basis to challenge the finding that a suitable geologic environment at depth provides the most sound and secure means of isolating the waste, but options old and new deserve to be re-examined. Technology and innovation have solved lots of age-old problems and it would seem only reasonable that there is additional knowledge to consider.

The logic would be that if we can refresh and defend the most viable option(s) we could bring renewed legitimacy to the task of disposing of waste and a societal issue that has not received its due. We then would need to apply all we have learned about how to best engage and collaborate with each other to find a suitable host location(s) to meet a commitment that we have grossly mishandled.

You do not

like it.

So you say.

Try it! Try it!

And you may!

If the hunger is there, it is possible to serve up Green Eggs and Ham in a way that is socially responsible, technically feasible, and economically reasonable. And it may go down better than one may think.

The End.