Episode 6

Kara Colton

Director of Nuclear Energy Policy at Energy Communities Alliance

A Look at Communities Affected by Federal Nuclear Waste

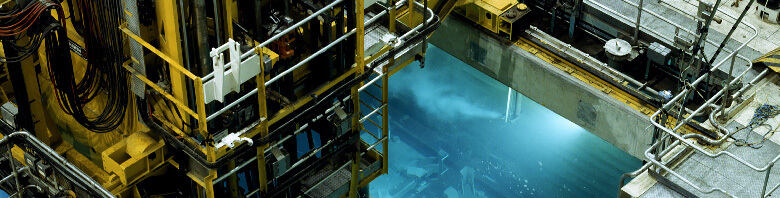

In this episode, Kara Colton, Director of Nuclear Energy Policy at Energy Communities Alliance, discusses the problem of how to dispose of federal nuclear waste at 16 locations nationwide.

Note: This transcript is the raw transcript of this podcast. Minimal edits have been made only for clarity purposes.

Kara Colton (00:10):

So the objectives for these communities are basically that they want to make sure that the waste is being dealt with responsibly, that they’re being engaged meaningfully, and that it’s not a federal policy of decide, announce, defend, which unfortunately has existed in the past.

Narrator (00:29):

Did you know that there are half a million metric tons of nuclear waste temporarily stored at hundreds of sites worldwide? In the U.S. alone, one in three people live within 50 miles of a storage site. No country has yet successfully disposed of commercial spent nuclear fuel, but it’s not for lack of a solution. So what’s the delay? The answers are complex and controversial. In this series, we explore the nuclear waste issue with people representing various pieces of this complicated puzzle. We hope this podcast will give you a clearer picture of Nuclear Waste: The Whole Story. We believe that listening is an important element of a successful nuclear waste disposal program. A core company value is to seek and listen to different perspectives. Opinions expressed by the interviewers and their subjects are not necessarily representative of the company. If there’s a topic discussed in the podcast that is unfamiliar to you, or you’d like to more closely review what was said, please see the show notes at deepisolation.com/podcasts.

Sam Brinton (01:49):

Hello everyone. My name is Sam Brinton. I use they/them as my pronouns and I get to serve as the Director of Legislative Affairs for Deep Isolation. Our guest today is Kara Colton, Director of Nuclear Energy Policy for the Energy Communities Alliance, ECA. ECA represents the local governments of the communities hosting or immediately adjacent to the US Department of Energy’s federal sites involved in government-sponsored nuclear weapons production, and nuclear energy research. At some of these sites, DOE produced defense high-level waste through its reprocessing programs. This is the most radioactive waste and along with the used or spent nuclear fuel produced by the nation’s commercial nuclear power reactors, it is due to be disposed of in a permanent geologic repository. Welcome Kara, thank you so much for joining us today and it’s so good to see you again.

Kara Colton (02:43):

Thank you for asking Sam.

Sam Brinton (02:44):

So tell us a little bit about the Energy Communities Alliance. How did it get started and why is it so important?

Kara Colton (02:52):

So the Energy Communities Alliance was originally founded in 1992, and it basically was created to ensure that the communities that are hosting DOE federal facilities have a say and are engaged in the decisions that the Department is making in nuclear waste cleanup and these communities, they are the communities that have supported the national security mission from World War II to help create our defenses. And they are the communities that make sure that these facilities are still being run. And they’re in charge of making sure that their citizens in the communities, that they’re protected their health, their safety, the environment. So they make sure that the community’s priorities are expressed to the Department of Energy and that the Department of Energy and Congress, as they’re looking at different policies, that they understand what the communities that are most directly impacted, what those communities see the impacts of a policy might be.

Sam Brinton (03:51):

Can you tell us a little bit about the history of the relationship between these communities and the Department of Energy?

Kara Colton (03:57):

They didn’t have a lot of say about where these facilities were originally set up, if any, say at all. I would recommend anyone going and doing a tour of the Hanford site, for example, that explains the government came in, said to some of the people that were living out there growing stone fruits, you got, you got to, you got to go. And when I say you got to go, we’re going to come in with a truck and we’re going to raze your house to the ground because we’re building something and we can’t tell you about it, but it’s very, very important. And so you have these communities that have grown from that being the beginning of their experience with the Department of Energy and the weapons complex to being who they are now.

Kara Colton (04:36):

That I think the interesting thing about these communities is that so many of these people, they watch their mom or dad work out at the site. And then they went to school for again, at Hanford, where the team name at the high school are “The Bombers”, you know, there’s a sense of pride that they really did help forward the national security mission. And they need to be remembered because that waste is still there and we don’t have a policy to deal with it, and we don’t have agreement on how to deal with it. And so these guys were told originally, we’re going to clean it all up, don’t you worry. But frankly, it’s a little concerning because we’re not quite sure how we’re going to clean it all up.

Sam Brinton (05:17):

So what is the Energy Communities Alliance main objectives when it comes to nuclear waste management?

Kara Colton (05:23):

So the objectives for these communities are basically that they want to make sure that the waste is being dealt with responsibly, that they’re being engaged meaningfully, and that it’s not a federal policy of decide, announce, defend, which unfortunately has existed in the past. But also they want to take advantage of the fact that these are nuclear familiar communities, they understand what it is to be living around a site. They understand how many different players are involved and need to be involved, tribes that are being impacted, state governments, state legislatures, regions of the country, not just the state, then obviously the permission of building new nuclear is a huge thing, as well as we consider whether or not we’re going to take, put into place policies that are addressing climate change in a low carbon future. And nuclear needs to be part of that mix, but you’re going to have plenty of detractors.

Kara Colton (06:24):

And you’ve had States that have moratoriums on new nuclear development if we can’t figure out the waste piece. And you know, one of the things I find most interesting about that this whole issue is that it’s not really a technical problem. It’s more of a political problem, but when you hear nuclear or nuclear waste, people might think about Chernobyl or Three Mile Island and they decide it’s the green glowing gook from the Simpsons. And they don’t realize like a piece of nuclear waste could be easily identified as a glove or a broom, for example. And so there’s so many preconceived notions and you know, the communities that we represent, they, they recognize that that’s how people might look at them too, or their kids that are going to school around the site. So, you know, these are, there’s such an interesting issue here because you really are finding beyond the technical, which should make people feel better, but it’s political, it’s the trust factors, it’s the relationship building, it’s the engagement. And it’s flexibility, which is an issue, huge issue, I think, that needs to be talked about.

Sam Brinton (07:38):

There are a hundred directions that nuclear waste disposal could go. And you and I know that, but local governments have a lot of different impacts and you have to try to focus them. So what other ways that you personally have been able to bring some kind of focus?

Kara Colton (07:53):

It’s building trust. It is not a technical challenge. It is literally getting people to speak to one another and allow flexibility in the conversation and respecting each party and the perspective that they have. So, you know, what a tribe might say in Idaho, for example, around INL could be 180 degrees from what the local community says, which could be 180 degrees from what the AG [State attorney general] says when they say, Nope, sorry, no, no small amount of reactor fuel can come in for us to do tests with. And I think that the way that ECA has been trying to address it is honestly getting the right people to the table. And sometimes right people to the table could be 250 people in a room talking about a new initiative. And sometimes the right thing could be a meeting around a site specifically where you’ve spoken with the different community representatives.

Kara Colton (08:55):

And, you know, there’s going to be all different perspectives, even within that one community, and make sure that people have the time to express where their concerns are, what their priorities are, what they’re afraid of. And there has to be a common understanding. This is tricky, a common understanding that there is no common understanding of risk. And so when everybody comes to the table, it’s important that each group gets to say, look to us, this is risky. At the community, nobody wants to hear anything coming straight out of headquarters without knowing that headquarters and site staff, that people that are living in the community from DOE are also engaged in that conversation. So there, you know, there’s so many different parties, like you said, and I think sometimes it’s as simple as getting the right parties at the table. And, you know, the federal government has a little bit of an extra responsibility because they need to make sure that the resources are out to all of the different groups that will be impacted by the policy decisions that they make so that those groups can participate.

Kara Colton (10:03):

I mean, you have some newly elected mayor of a town who doesn’t know that much about nuclear waste. So, make sure that those groups have the resources they need to get educated. And sometimes the Department should put aside resources so that the community can say, you know what, we’re going to hire an independent third party to look at the data. Not that we don’t trust the DOE, but it’s easier for us to advocate for a new project if we can say, look, we got this, we trusted, and we also were able to verify it and DOE needs to understand that’s just as much part of the process to build support.

Sam Brinton (10:41):

You talked about tribal governments, you talked about local communities, you mentioned site staff. So it’s not actually just the Department of Energy complex. It’s actually a lot of people living, breathing, working there and there, of course, you’ll have the industry. You probably have other organizations who also are having concerns, right? So what would help improve the lack of trust and open the line of communication between all these different parties and different people?

Kara Colton (11:07):

Well, I think definitely there just needs to be, and it’s simple, it sounds so simplistic, but there needs to be more engagement. There needs to be more engagement all the time, frankly. And you know, you mentioned all the other groups, I would also add to that, you know, you said industry, industry/contractors. So you need, like, there needs to be messaging that flows down and flows up, right? So if we’re talking about picking a new site for a nuclear waste facility, you need to make sure that the community is interested. And this is something we just recently, ECA, just recently was talking about, and that is, we’ve had conversations with the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future. We know that Yucca Mountain is pretty much stuck in a stalemate. And so the countries that are like let’s, re-look at this again, it was not, it wasn’t even the first relook. It was, I don’t even remember, how many relooks we’ve had since ’87.

Kara Colton (12:09):

So we brought everybody together, but they didn’t only do it in Washington DC. They did it around the sites. They went to larger commercial centers. They went into the areas where these facilities exist, which aren’t super well populated. I think those things need to happen. We need to make sure we get around the country. And also there needs to be, there needs to be some love given to the country, to the communities, and the States that are hosting these facilities already. There needs to be recognition that you’ve done something for the country thus far. And it’s worth listening to you. In contrast, when the Department of Energy is looking at doing new contracts, you know, there should be a community commitment clause in there that says the contractors that are doing these work, this work, you know, value the community where you’re working. Value the community that is supporting the national effort to not only clean up the waste but, you know, without a facility like INL, the nuclear Navy, where’s that gonna go?

Kara Colton (13:17):

Where’s that waste going to go? And if they don’t get it out, do we still have a nuclear navy running around for as long as we might need it or want it? And also, are we looking at the nuclear Navy and how they’ve been able to have a fleet that’s run so well for so long? I mean, there’s so many different examples of things, and I don’t know that we have done a great job telling that story of success. It’s very often a pitch like, “Yup, new nuclear would be great because it could reduce carbon emissions, but oh, the waste problem. Okay. Maybe not.” And I think there needs to be better, good stories of what can be done, Deep Isolation and being able to, to put it underground and then pull it back up. I mean, technologically, like, like we talked about, it can be done.

Kara Colton (14:12):

And it’s important to look back at those lessons learned, especially now, because at least on the cleanup of the defense weapons complex, we’re now at the point where it’s the hardest work. Right, work has been going on. It’s been 30 years of the Office of Environmental Management and successes there and successes our community celebrates right along with the Department of Energy. But now we’re, now we’re at the harder stuff, so it’s gonna be more difficult. And so we do need to find a way to express what our different concerns are, but demonstrate that there are a lot of people on the same page, that there’s a good path forward. There’s an opportunity here that shouldn’t be missed. And then to get back to what I forgot I was going to say earlier was, you know, looking at siting new facilities, one of the things that was always considered was how are you going to find a community that’s interested who, you know, I think during the Blue Ribbon Commission, you had a lot of people say like, really who’s, who’s chomping at the bit to have one of these facilities in their community.

Kara Colton (15:18):

Maybe we don’t need to start from scratch. Maybe we look at the communities that are already comfortable with nuclear and say, “Hey, you guys have a skilled workforce. You have a lot of retirement across the DOE complex coming right now, the silver tsunami. You have COVID has led to obvious job issues. And you have a lot of focus on STEM and the Department’s been great at getting resources out into the schools for STEM education.” And let’s wrap all of those things together and deal with economic development opportunities. And let’s look at the communities where you’re not starting from square one. And when the Department of Energy suggested the Global Nuclear Energy Partnership back in the early 2000s, ’06, ’07, you had 11 communities raise their hand and say, “Hey, you know, we, we, we might be interested in hosting a reprocessing facility”, and then go a step further and say, “Okay, that’s great. What would you, what is it that the community sees as the opportunity?” And the communities say, they say, “Well, we would love to have the reprocessing facility. And we’d love if you guys could maybe introduce a new national nuclear mission at the lab that’s here.” So there are a lot of win-win opportunities here that go all the way down from ensuring that the environment is being, is being managed, that the stewardship is there, to training the next generation of nuclear workers, be it on a waste facility or a generation facility.

Sam Brinton (16:48):

So when you’re talking about high-level waste in the communities you’re dealing with, what is the language that you use to describe it? And why is it called that in the first place? I know that it’s important to have a common definition when you’re trying to build consensus.

Kara Colton (17:01):

High-level waste from the defense perspective is the waste that results from reprocessing activities, basically, plutonium-related reprocessing activities as part of the weapons production. It is the stuff that needs to be isolated for thousands of years in order to protect human health and the environment. And the way that the Department of Energy in the United States defines it, and this is an ECA initiative that we’ve really been pushing on, I think we started maybe 2014, 2015 talking about, is that we have learned, going back to what we talked about before, over time, it has become scientifically clear that some of this waste that was considered high-level waste, based on the fact that it was a result of some sort of reprocessing activity, it’s actually not based on constituents level. It doesn’t need to be isolated in a deep geologic repository anymore.

Kara Colton (18:05):

And that is what the waste classification discussion is, that we in the communities have been having. And it’s one of these alternatives. It’s one of these, let’s look at what we’ve learned over time and see whether or not there are new alternatives for safely dealing with this waste. So most countries that are dealing with high-level waste and nuclear waste period, define their waste categories based on what the constituents are, how radiological are these constituents, and do they need to be isolated? How do they need to be isolated? And in our country, the defense high-level waste is defined by where it was produced, where its origin was. That’s not how it works in the United States. We now have it where something that’s in a tank in South Carolina versus something in a tank in Washington, regardless of whether or not they’re the same level of radioactivity, they’re going to have to be dealt with the same way, even though they really don’t need to be dealt with exactly the same way.

Kara Colton (19:10):

And that limits the ability to make decisions about waste. Somebody in South Carolina, where this waste interpretation is being applied right now, it’s going to be eight gallons. It’s a very small amount, but they’re pretty darn sure, I dare not say a hundred percent, but it could be a hundred percent sure, that the waste that’s been removed from some of these tanks in South Carolina are not high-level waste based on what their constituency, their constituent levels are. And then it could potentially go to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico (WIPP). The people in WIPP, the people in Carlsbad that host that facility, they’d love it. They’d love to have this continuing mission. They know what they’ve gotten by being basically the crown jewel of the DOE facility and, and handling waste. And then you get into the problem, of course, does the state want it, do the surrounding communities want it, and then we get back into the political argument, but technically speaking, it should be able to go down very safely there or to Waste Control Specialists or out to Utah.

Kara Colton (20:19):

And the way the Department is talking about doing this, and we support them looking at the alternatives, we support a full evaluation of it. We’re not saying, go do it. We’re saying evaluate it. Let the communities that will be impacted, understand what those impacts are going to be. Let’s have a long discussion about what happens, but ultimately, it would allow, if the evaluation proves out what we think it will, it will allow waste to be moved off-site more quickly. It will save money. Right now, the high-level waste issue is the governments. Well, maybe before COVID, before COVID, I feel comfortable saying it was the third-largest federal liability, for the country was dealing with this way. So we could cut that money and the taxpayer liability, we can move some of that waste. There’s been progress on the ground, but we keep paying more because we’re not moving waste.

Kara Colton (21:13):

We now create storage areas for this waste that would have been moved long ago. And we can then focus on other, other aspects of either building new nuclear facilities or just focusing more on a harder cleanup project that needs to be dealt with when we know that this one is a safe alternative, that can work. So the Department is moving slowly, steadily. They have made an absolute commitment. Kudos to DOE on this one, they’ve made a commitment to engaging with the local communities and not making any change in any, any program or the way that they’re dealing with high-level waste at any of these sites until there’s been full-on discussion with, with the parties that are going to be impacted, which will be the local communities. And the States will obviously get involved as well.

Sam Brinton (22:02):

How does this reclassification issue raise concerns for the communities?

Kara Colton (22:07):

Gets back to the very basic trust is a huge one and the need for flexibility. So for example, you have people who think that it’s a lesser cleanup. Why was this considered high-level waste before? But now you’re telling me it’s, it’s just like, transuranic waste. Why did you say that before we have to bury it in the ground for thousands of years? And now you’re telling me it can go in salts. These are real examples of what DOE is negotiating with the same with communities over time. And sometimes going back to the fact that over time, things can change, they might be in agreement that, Hey, you know, cleaning this up to industrial, to an industrial park is exactly what we, the community, now think will be really good for us. Or the Department of Energy, for example, on the high-level waste thing says we would spend so much more money.

Kara Colton (23:01):

Another one of the things is the technical definition, is about breaking out certain constituents from waste. And so the agreement in some places is that it all goes, it all absolutely goes. We break it up and it all has to go. But it turns out that you may be risking a worker’s safety if you try and take out the most radiological components, instead of keeping them together where they will be buried together. Right? So does the risk go up if you’re, if you’re splitting these hairs. Again, it gets back to, like I said, the trust issue. So if people are looking at the site over time and they say, “Oh, well, you were supposed to have Yucca Mountain open and accepting waste in 1998. And now it’s 2020. Why am I going to trust that you guys are going to do what you’re saying you’re going to do?”

Kara Colton (24:01):

Even if you have the state support, you could have a change in administration. You can have a change in policy, and there you go, you’re back to square one with somebody saying, well, that’s the last time I’m going to go down this path with you guys. And that’s, that’s an unfortunate, scary thing I think, because political it’s the politics that have made this very difficult and the politics isn’t going anywhere. So the trust it has to be trust. And it has to be we have to allow, and there has to be trust that the resources exist for us to relook at some of these things. And everybody needs to be prepared to come to the table and say, this is what I don’t trust. And this is how I could trust it. This is who I would want to hear it.

Sam Brinton (24:49):

So for our last question, tell me a little bit about the future of nuclear waste and engagement and how we can honestly all make it more successful.

Kara Colton (24:59):

Everybody I’ve met wants to do the right thing. I really believe that of all of the different conversations. Not everybody agrees on what that right thing is, but people want to be responsible and clean this stuff up. And many people want to see a new nuclear mission across the country. And so I think first and foremost is you gotta, you gotta get to that community. You gotta get in there, you gotta get the right people. And that might be the person running the science museum. It might be a teacher in the local school that, you know, sees this massive employment opportunity for their students and wants to see young people stay within their community and find out what it is that that community is, is looking to do and who they want to be.

Kara Colton (25:50):

Zion, for example, they don’t want the waste there anymore. They don’t want it. And it’s just taking up space. So they’re probably not the best community in the world to say, “Hey, you know, we thought maybe a borehole could be cool here.” I think people have to listen. I think you have to get the people in the room. You have to have an iterative process. I mean,y it’s not going to be one meeting and we’ve covered it all. And it’s not going to be one meeting with one group and you covered it all. You have to be honest about what the potential pitfalls are. What are the challenges? How do you speak to those challenges? You have to talk about emergency planning. I mean, things that, that do make people a little bit antsy, they have to be addressed. You can’t pretend that emergency planning doesn’t need to be part of the conversation, but you also have to look at this community.

Kara Colton (26:41):

Let’s take, let’s take Yucca Mountain, for example. So the community of Nye County, they want it, they see all the economic opportunity. They feel like there’s, there’s no other piece of land on earth that’s been more studied. The NRC did all of its safety evaluations. And yet you have the communities outside of the people, right adjacent to Yucca Mountain, who don’t feel that way. They’re scared about the transportation routes. They’re scared about what if waste going to be liquid? Is it going to be solid? What if a plane hits it? What if there’s terrorism? Like all of these things, which are very uncomfortable to think about because nuclear, ah! But we’ve been doing it. Like there are waste shipments moving across the country all the time safely, and we just need to get all of the facts out and trust each other.

Kara Colton (27:32):

Trust each other that I’m going to listen to what you’re saying, and I want you to hear me also, and we may not agree, but let’s meet again in three weeks. And while that happens, identify champions, identify champions in Congress, identify champions in the Department, identify champions in your community, identify champions in your region. It’s an exciting time. And it’s good that we now start looking for the new champions. And I think it’s we, you at Deep lsolation, me, the communities, the States, everybody, it’s, it’s going to be on us to help educate new lawmakers. It’s going to be up to us to educate new elected officials at all of the different levels of people who are involved and the time is now. And I think we all need to understand that the waste and the new nuclear, they, they’re very related. And one shouldn’t inhibit the other. They should, we should work together in a holistic approach to nuclear.

Sam Brinton (28:38):

Thank you so much for joining us today, Kara, for pointing out the problems, but also putting them into context and offering solutions. Really grateful to have you here.

Kara Colton (28:48):

Thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate it. Sam always.

Nuclear Waste 101

Understand more about nuclear waste and its implications for you and your community.

FAQS

Deep Isolation answers frequently asked questions about our technology, our process, and safety.